The Edwardian era produced many eccentrics, visionary lunatics and wealthy dilettantes who straddled the line between innovation and psychosis. Among them was Jasper Lamb, an ex-Royal Guard who set himself an unusual task. Obsessed with respiration in all its forms, he decided to collect and bottle breaths from all manner of people, flora and fauna. Over a six year period he captured the exhalations of hunting jaguars, the gasps of lovers, the silent rasp of an oak tree, the dying breath of playwright JM Synge and over a thousand other volumes of spent air from every corner of the world. The breaths were 'displayed' to a frankly bemused public in stoppered glass bottles in the Regent Palace Gallery in the West End of London.

"Breath," he wrote in a letter to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, "is not merely a signifier of spirit. It is its vessel. When I collected your breath yesterday, I collected a minute part of your soul."

Lamb's breathing fixation was soon veering towards apotheosis. All the second-hand air he had collected was transferred to a single brass cylinder, which Lamb connected to a state-of-the-art diving suit. Inside the suit, he hoped to receive a powerful infusion from the spirit of every breath he had captured, an act he hoped would bestow on him godlike powers. Needless to say, the only change that had occurred when Lamb emerged from the suit was that he had contracted tuberculosis.

Little in art is truly dangerous. Radical as Tracy Emin's unmade bed may have been, no one actually died in it. Only one artist in recent years could lay claim to causing actually bodily harm in the pursuit of their vision.

Sammy Ridley pioneered an artistic technique he dubbed 'Quantum Portraiture' in which his subjects were blasted with streams of subatomic particles from a handheld particle accelerator. The image of the subject was then burned onto a surface directly behind, whether a canvas, a wall or a sheet of helium ice.

Ridley claimed this method allowed him to reveal the 'quantum essence' of his subjects, a remark that art scholars are trying to unpick even to this day. An exhibition of his Quantum Portraits was held at the Whitworth Art Gallery in 1987. It proved a critical and popular success (George Melly called it "thrillingly scientific") and was due for a transfer to the Tate when disaster struck. The twenty-four people who had been the subject of Ridley's portraits began to exhibit signs of cancer. It soon transpired that the blasts of radiation Ridley had subjected them to were to blame.

A minor scandal erupted, exacerbated by the death of his first subject, Ridley's fellow artist, Sasha Peck. The Tate exhibition was cancelled and Ridley found it difficult to work. He experimented with the idea of 'Quantum Landscapes' but met with (obvious) resistance to the prospect of irradiating vast areas of the English countryside in the name of art. His final work was a Quantum Self-Portrait that blasted the image of his face through twelve sheets of concrete.

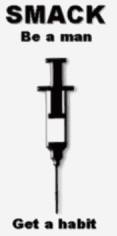

Dragoncrew Arts Collective are used to difficult subject matter. In 1999 they produced a musical version of J.G. Ballard's disturbing cult novel Crash in association with Fairchild Theatre. Their newest work is an exhibition detailing the long and intriguing story of that most potent of substances, heroin.

"You could almost say heroin has an image problem," says Shauna Boardman, Creative Director of Dragoncrew. "Its obvious association is with crime and desperation, but scratch the surface and there's a whole world underneath."

This world is laid bare in the exhibition, which brings together manuscripts from famous junkie authors (including William Burrough's infamous Journeys with a Flute), images of heroin use throughout history and even adverts from smalltown American newspapers where drug dealers openly advertise their wares.

But most striking of all is the heroin-inspired range of clothing on display. Designer Martha Stein has created suits made of syringes that turn the wearer into a bizarre bipedal porcupine.

"I like the idea that these clothes are dangerous," says Stein. "When you wear a coat made of needles you're presenting five hundred little reasons for people to take you seriously."

With thanks to Rod